Interview | Lindsey Moran

Lindsey Moran is an artist living and working in Liverpool. In 2022, she was awarded the Ushaw Residency & Acquisition Prize at Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair. As an educationalist, Lindsey has a love of buildings of historic or educational significance. Places that celebrate or house collections that both inform and educate.

Lindsey has exhibited widely; recent highlights include the New Light Art Prize, Royal West of England Academy Open Exhibition, Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 5th Global Print Biennial Douro, Portugal and Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair. She gained a BEd Hons in Art and Education at University College Chester where she specialised in Printmaking and received the Academic Award for Art. She was invited to stay on as a Research Fellow to investigate ‘The Role of the Computer in Fine Art Printmaking’. Technology still plays an intrinsic role in her printmaking today.

We are delighted to welcome you as artist-in-residence at Ushaw Historic House, Chapel and Gardens! Were there any aspects of this residency and Ushaw House, chapels, library or gardens that you were particularly excited to explore?

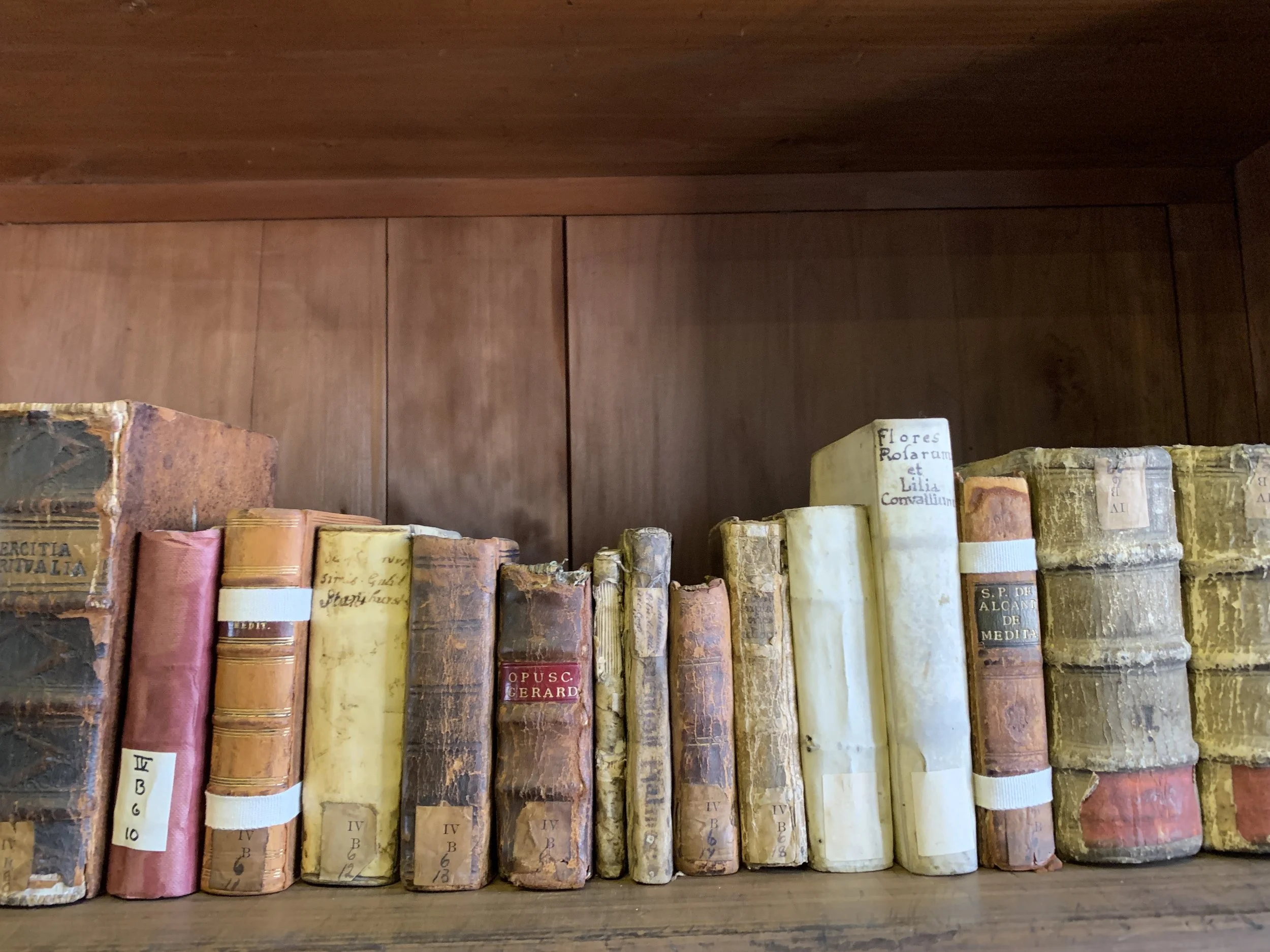

I think the whole visit was initially quite overwhelming because it's such a hidden gem and there's so many treasures. Although it was for two weeks, I was trying to focus and immerse myself in certain aspects. The library, being an educator, was something I was absolutely drawn to and had to revisit. The collection of books is just incredible! I think it was also about having the font of knowledge that is Matthew, the Librarian, with us who was able to really tap into what we were looking at and what we were interested in as printmakers. Even within the collection it was very much a history of printmaking.

The architecture! Obviously in my work I'm passionate about places of history but also places that have collections. Ushaw was just that. To really understand more about the Pugin family, the architects, and the flamboyance that was in this place. I actually went to Ushaw when I was a sixth form student and I think it was fascinating for me as an 18 year old but things don't jump out and hit you the same way as when you're an adult and you've lived a little bit. To be able to go back and actually see the treasures I'd missed! I spent a lot of time in the chapels, watching the light change throughout the day. It just kept giving and I still feel that I've only scratched the surface. My camera never stopped! It was a magical time.

Lindsey during her residency at Ushaw Historic House, Chapel & Gardens

It’s fascinating that you have visited Ushaw Historic House, Chapel & Gardens previously because I think you're the first person that we've had in residence to have been there before. It’s interesting to have this unique sense of time changing. Although it’s the sort of place that doesn’t change in many ways, you as a person have changed coming back to Ushaw.

I think I’m seeing it in a very different way now because as a teenager, you don't go to look at the architects, you don't go to look at the collections, you’re with your friends having fun. But I did actually have some key memories from my first visit but to go back and then to be reintroduced, it's a really magical place. The history there and the quality of education is phenomenal. The collection itself, it just needs to be shared with more people.

Lindsey during her residency at Ushaw Historic House, Chapel & Gardens

You were awarded the Ushaw Residency & Acquisition Prize for your artwork Reawaken II, exhibited at WCPF22. Could you talk more about this artwork and the inspirations of architecture, site and history?

That particular etching is from my Oxford Light series and is based on imagery captured from Oxford and its history. The Natural History Museum, which is linked to the University in Oxford, is a really precious place; not only the architecture itself but the collections too. The building, I think, is classed as a temple for science and it absolutely is! The building has been described as a true temple for science and it absolutely is! Engineering wise, the first roof was made of steel and was incapable of supporting its own weight and had to be replaced. So it's not only the journey these buildings go on, but also the history behind the collection and how it’s evolved. If you're not familiar with that museum or the artefacts, it raises the questions to encompass the collection, the artefacts, and the architecture.

Reawaken II, 2022, Photopolymer etching, 52 × 25 cm, Edition of 25

How did this piece come about, given its site specific nature? Was the Natural History Museum in Oxford a space that you chose to make work in response to, or was it based on a commission?

I like to go to places of historical significance and I was invited to exhibit in Oxford at a gallery with another series of works about grand interiors, some of which have been exhibited in previous Woolwich Contemporary Print Fairs. I hadn’t been to Oxford so I had to search the history and identify the key buildings, which I then wanted to visit and I was blown away by The Natural History Museum. Each time you go, you find something different. A bit like Ushaw, you're able to immerse yourself in the history of a place and the collections.

What also puts the cherry on the cake is the architecture and the significance of the environment that you're in. It's a number of things that merge. So yes, it was my choice of subject matter. Natural history museums are often the first places I will seek out in any location that I go to.

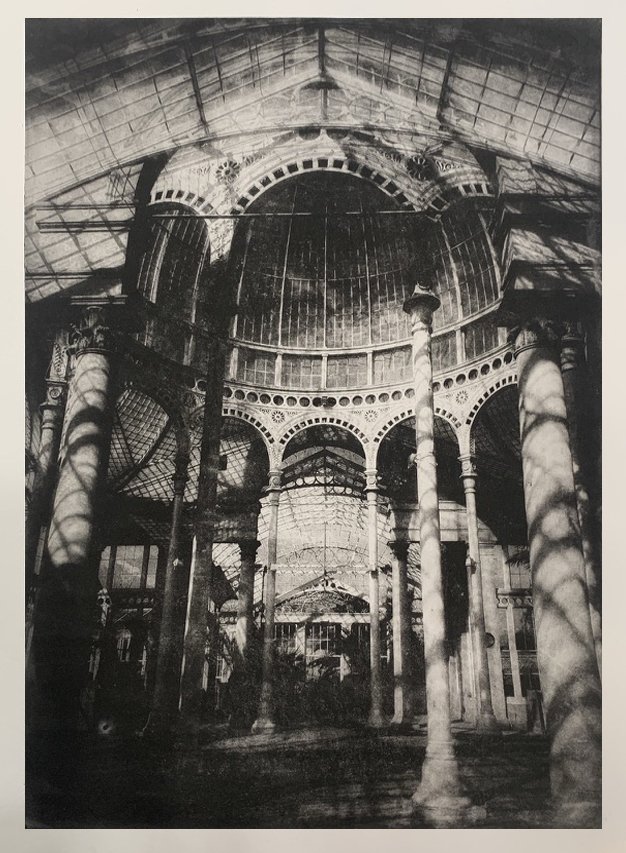

The Great Conservatory II, 2021, Photopolymer, 35 × 47 cm

There is a dramatic stillness to your artworks, capturing spaces such as The Natural History Museum, which are normally populated by lots of people. It is as though we are given a glimpse into these grand architectural spaces just before they open, a moment of stillness as the morning sunlight casts a shadow through the window. It also creates a tension as the images are at once peaceful and still but this also emphasises their morbid qualities and the passing of historical time.

Can you talk about these tensions at play in your work?

The word ‘evolution’ is a really important aspect, coupled with the evolution of the work. As my imagery evolves and because of the links with technology in how I work, my iPad is like my own collection of which I'm the curator. So when I go to places like museums, I’m tapping into what is of significance in the exhibit. A key one down in Oxford’s Natural History Museum is the tuna fish skeleton, the blue fin. It's the history of the journey, the myth that went with it and the legend about how it got there. There's so many different aspects but what I do is strip back the imagery. So you actually look at the features that are there and how the light illuminates the key aspects, whether it's the structure of the artefact or the structure of the architecture. Atmosphere is also important and that's linked to the history of printmaking and photogravure as well. That old master type of feeling, a real strong sense of composition.

It is a point in time, nothing is permanent and everything changes. A lot of things have become digital, which is great and I'm a great believer in technology and AI. But I also think there's a time and place for these collections and how to capture them. That's what I want to do through my artwork, really capture that history and its purpose.

V&A Stairs, 2021, Photopolymer, 35 × 47 cm

Reawaken II also brings in the morbid qualities of the specimens and museological collections, which are mausoleums in a way. I think the monochrome imagery monumentalises and memorialises these spaces as well. I wondered if this is something you've been thinking about?

I think it's a combination. You only see the tip of the iceberg in collections of most galleries and museums. Therefore, it's a snapshot and it's often the audience ‘grab’ that you get to see, the bit that's going to make people stop, not necessarily the actual science and anthropology that are linked to it and the discovery. At the Oxford Natural History Museum, something as simple as the pillars around the building, each pillar is a decorative stone of the British Isles. A lot of those decorative stones you might not be aware of or you might not ever see. Whereas for me, the cornices and the botanical carvings are interesting because of how they combine the two to celebrate and educate.

The education part is often the bit that draws me in, in the sense of all these different components that they're trying to portray. I understand there is this morbidity and mausoleum element, but it's also a celebration. To me, it's more celebratory as an educator.

Linnaeus and the Skeleton Parade, 2022, Photogravure, 21 x 30 cm

As someone who's curious, I want all the next generations to be equally as curious and sometimes technology can make people quite passive. It's a butterfly effect of how people look at things through their phones. You don't want to lose the capacity to see and feel things.

To me the education aspect is really key and to raise a question. There's nothing more magical than seeing children running off to bigger artefacts, which are the size of a giant spider crab or something. I suppose my educator hat comes on a little bit as well as being an artist when I'm in these environments and I am subconsciously drawn to things about learning culture, history and evolution.

What drew you to printmaking?

Whilst I was doing my degree, I was specialising in painting, and my interest in scientific evolution came into play then. I was looking to put scientific elements within paintings, and then a natural shift was screenprinting and putting that within the canvases. When I went into the printmaking department, I just fell in love with etching and the relationship between the evolution of the image on the plate, working with acid. Now I use nontoxic processes but it was sulfuric acid at its best back in the day. I worked on steel, drawing scientific diagrams into plates.

Lindsey at work in her studio

What I loved was the unpredictable nature of printmaking, but also the qualities that you could get from it, such as the layering. My subject matter also married better than in painting. I had a printmaking lecturer who taught us great techniques but he laughed at me and said, “You've taken the rules, you’ve squished them up and then you have re-established them.” It's because I ask questions and push boundaries, such as ‘why can't I do that? Why have I got to put that on? Why should I use that chemical?’

I was asked to stay on to do a research fellowship on the role of computers in fine art printmaking. That's really where the journey began because I got to work with a computer technician. I needed to learn some of these facilities to be able to achieve what I wanted to do technically in my plate making. So we set up the computer lab in the art department in Chester. Thinking back now that was 1994 and something as basic as flipping an image in Photoshop would take overnight. How I had the patience, I do not know! But to see how technology has progressed, again, it's another evolution. Now, technology is always being integrated in the processes that I use and that's why the marriage between photography and printmaking still remains very much in the main of how I approach my work.

That's how I got into printmaking and constantly worked at it to refine the processes. I then got into using solar plates and exposure units to try and make my practice less toxic.

Lindsey at work in her studio

Could you tell us a bit more about your practice and the processes involved in creating your prints?

I don't like to use other people's imagery, I like everything to be my own. Originally, when I was layering images in my etchings and looking for scientific aspects or architectural aspects, I wanted the photographs to be my own. So I wanted to get better at photography. Although on the photography side, I am self-taught, I looked heavily into it and got better equipment as the years went on.

Then on the printmaking side of my practice, I got into working with solar plates 10-15 years ago. I did a course at Edinburgh Printmakers, which was amazing and I really learned a lot because everything can go wrong with my process. It can be the timings, the exposure, the washing out the plate, the printing, the pressure of the press, and so on! However, I like a technical challenge, I always have done and I'm quite proud of that.

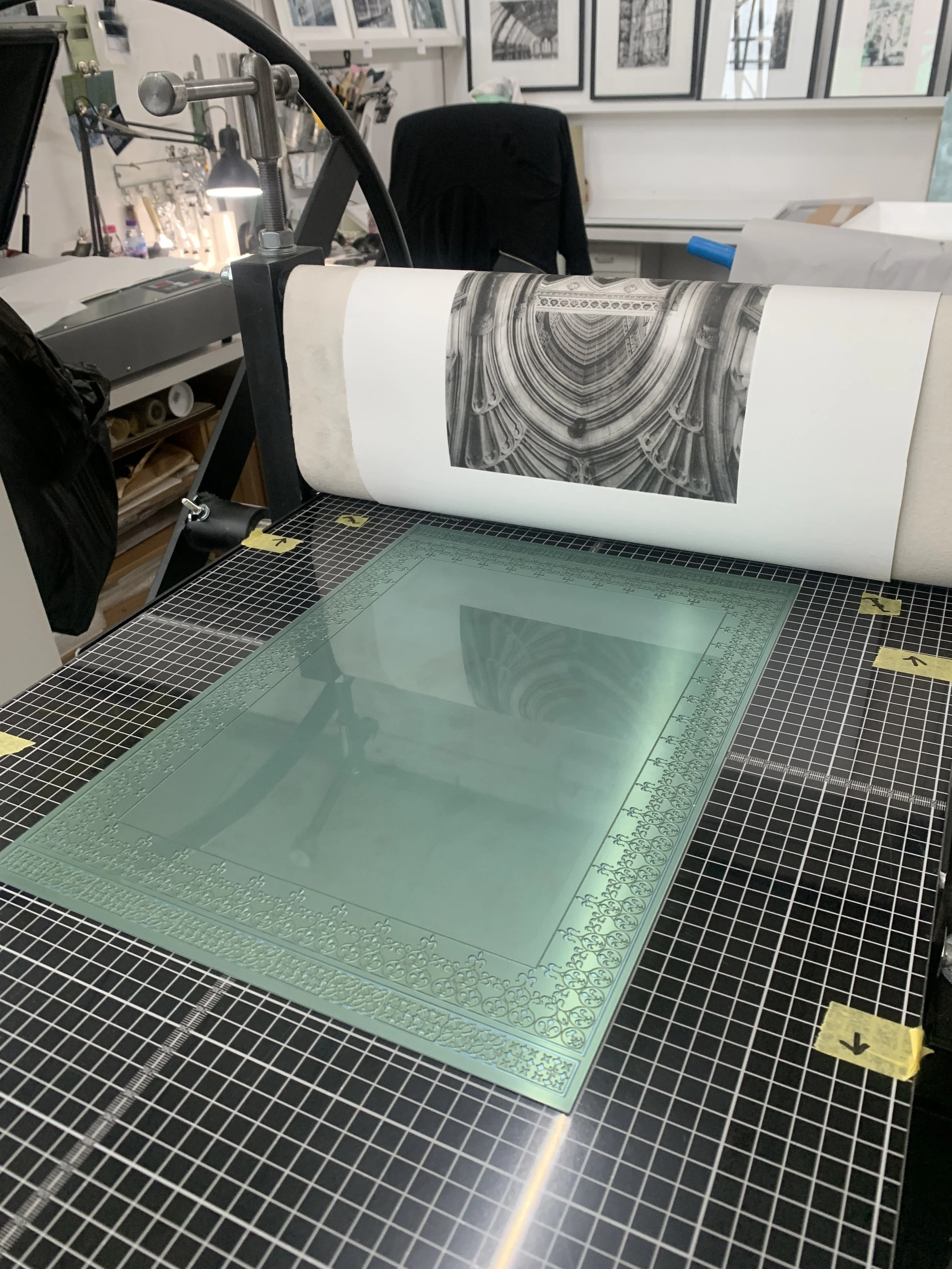

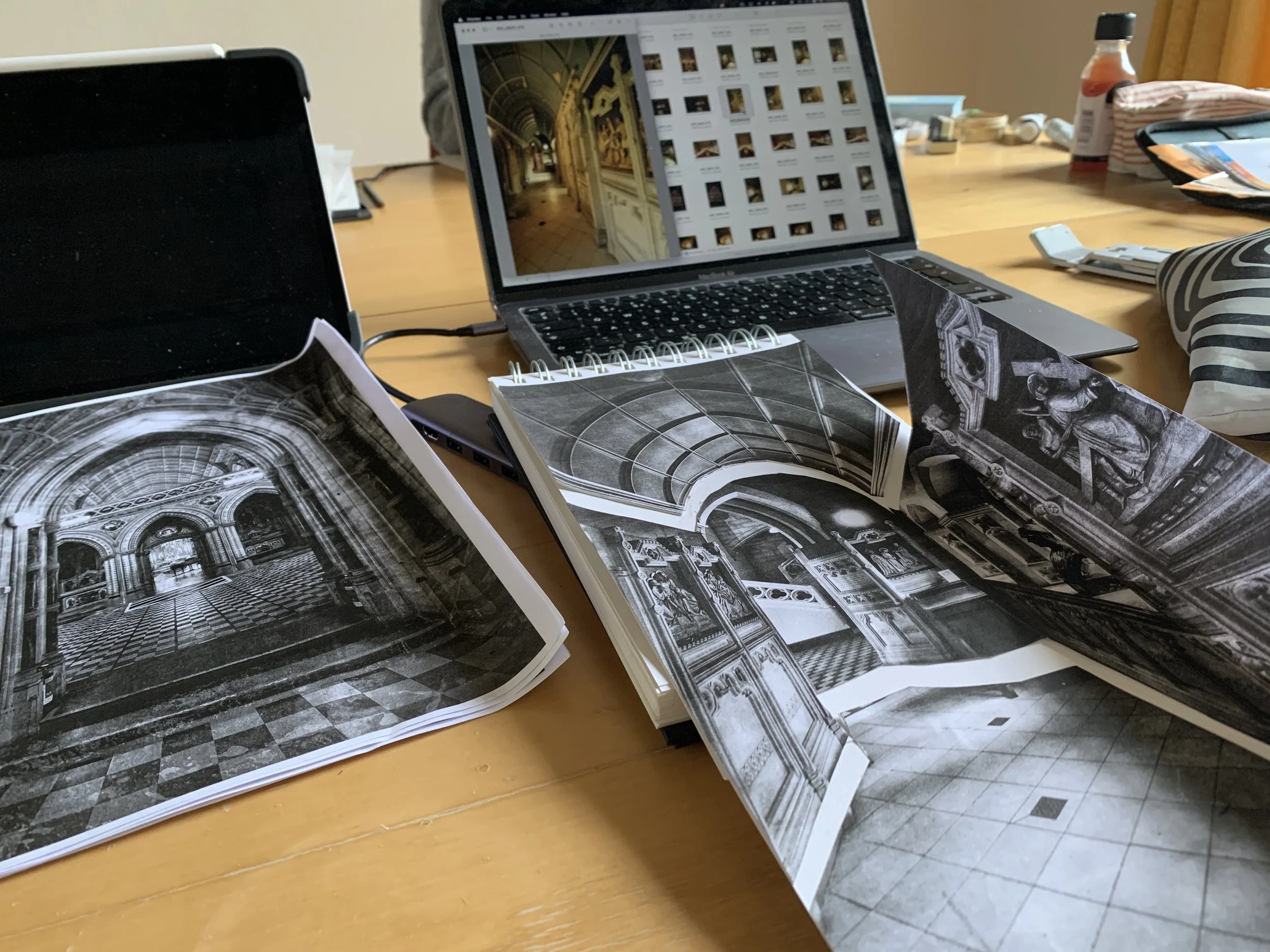

Works-in-progress in Lindsey’s studio

At the moment I'm investigating laser cut woodcuts with the Ushaw material. The collection of photographs I’ve taken from Ushaw have all been organised in my iPad in different albums and I’m starting to strip back the colour and check out the compositions.

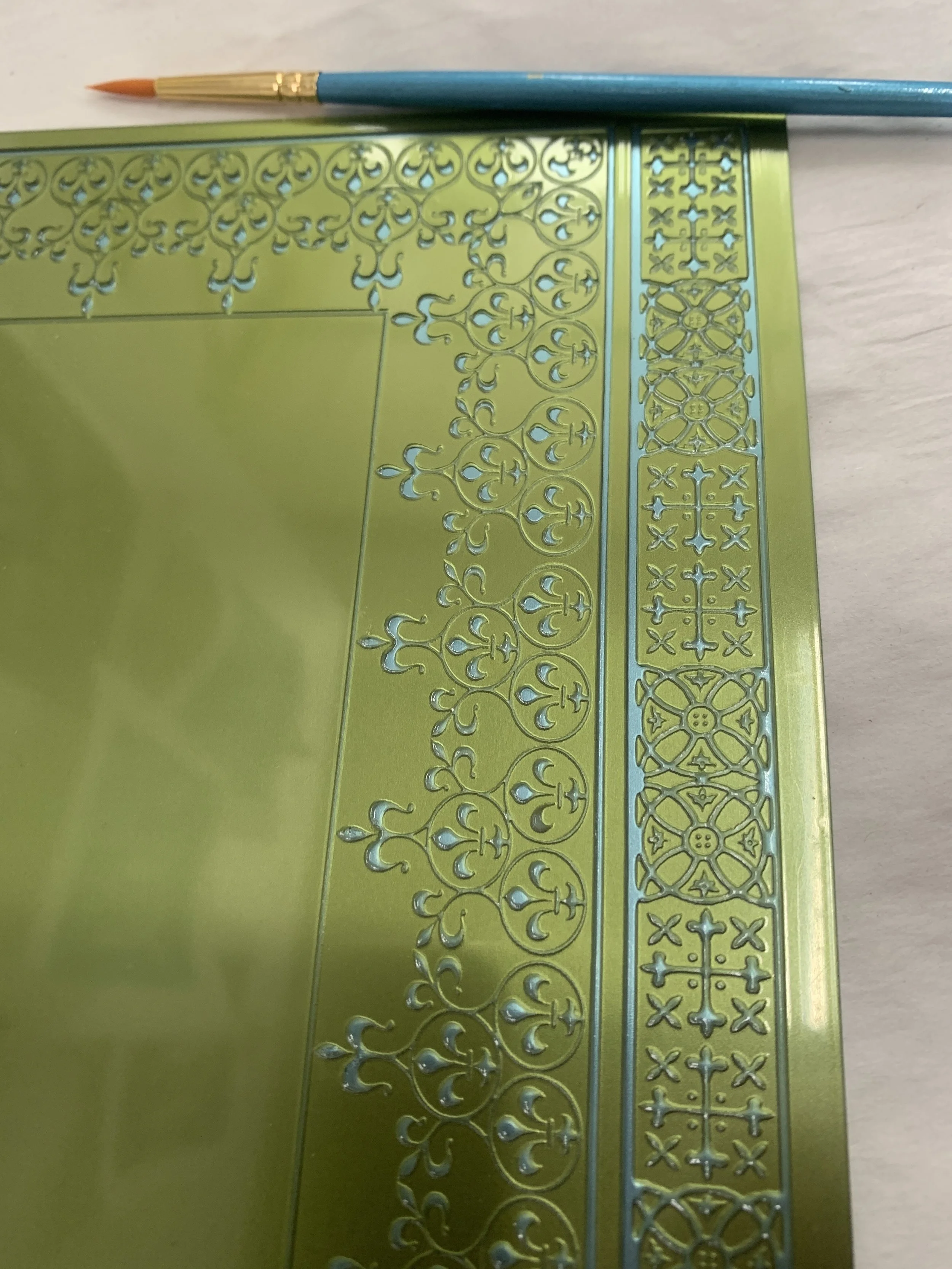

For me, laser cutting is a new process because I’d like to go bigger and also incorporate embossing. The manuscripts in the library that were hand drawn, painted and printed painstakingly by some of the original students, I almost want to flip that and take some of my imagery into a laser cutter where the machine is doing it for me. Showing the evolution of printmaking and how it is moving onto integrated technology.

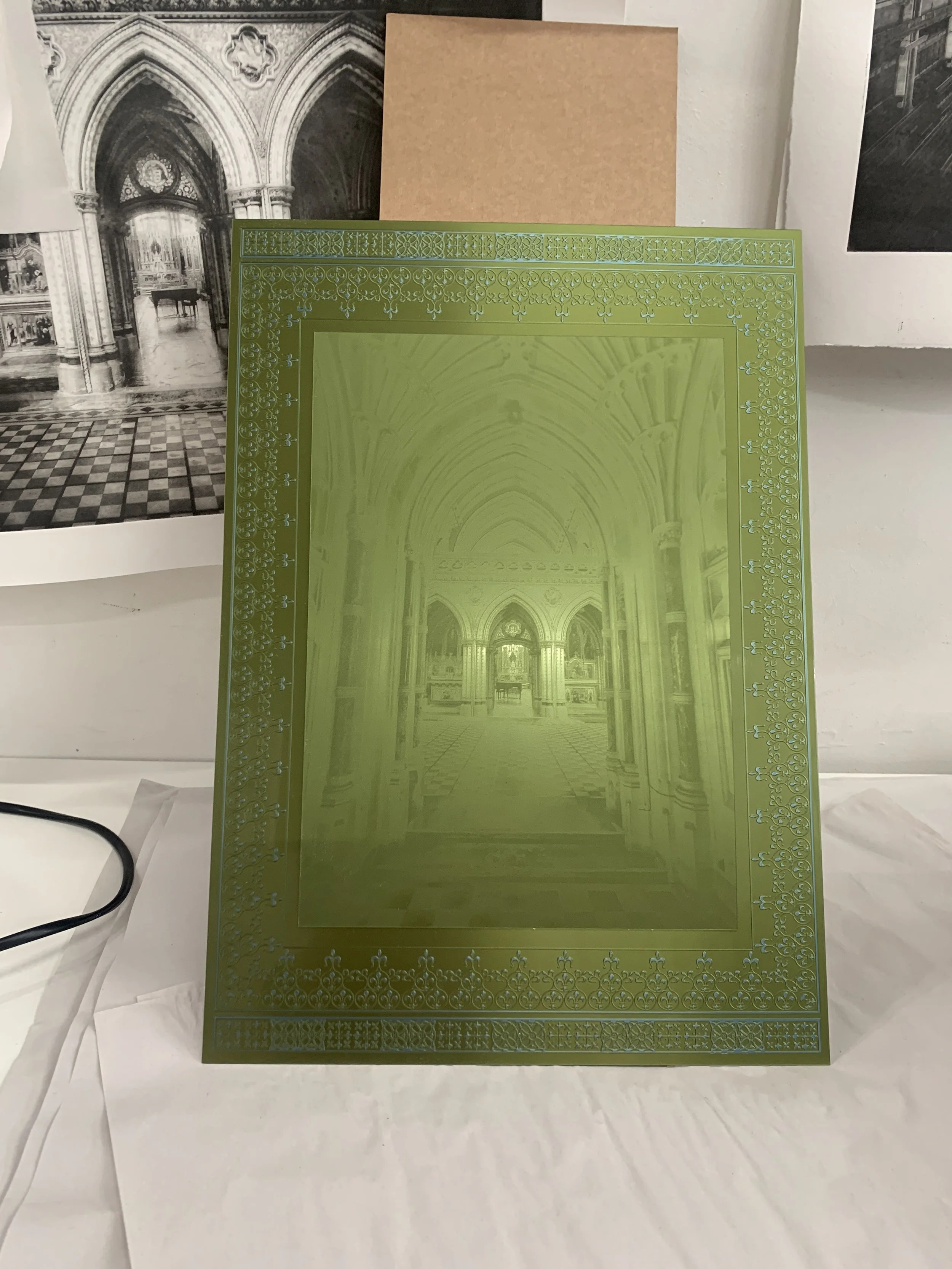

The next stage is to take a couple of them to be exposed onto plates and then print to see how it looks. That's just the nature of the journey. It's the immersion in the location and then the curation of the collection of imagery, some sketchbook work, and then taking them through to exposure on photopolymer plates.

Works-in-progress in Lindsey’s studio

Can you describe the technique of photogravure and your use of solar plates?

I share a studio in Liverpool, so I'm self-sufficient in that I've got my own vacuum exposure and my own press. I work on the imagery in Photoshop then I take it to my iPad, where I really refine the imagery until it's at a stage where I'm happy with it. It is then printed onto acetate. This transparency is then used on photopolymer plates, which are light sensitive but very delicate plates. I use an Aquatint screen because you have to put a matrix across the whole plate otherwise it'll wash out in big areas. This is a technique you can use for relief prints. The transparency is then overlaid in the exposure unit and exposed a number of times. Once they are exposed, it's washed out in water, which is great because the bits that haven't been exposed remain soft and wash away. Then you dry the plate and cure it with more exposure to UV light. Once it's hardened, it prints as an intaglio plate through a traditional etching press. That's where you go from contemporary to the traditional processes and I like that fusion.

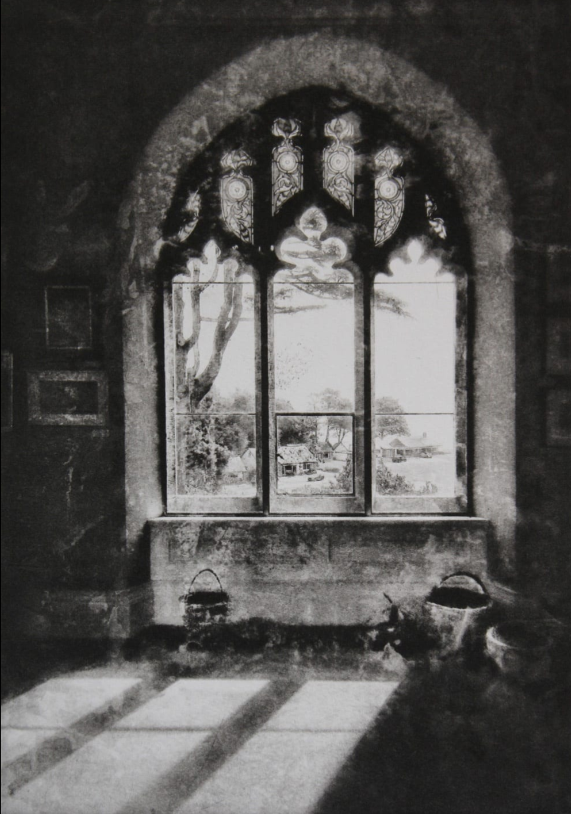

Window Light, Photopolymer etching, 21 x 15 cm

The use of light as a concept and method within your practice seems very important - the use of black and white photography, the alchemic reaction of exposing photopolymer resin, and the dramatic contrast lighting in your final images. Could you expand on the importance of light in your artwork?

I think drama within my work is where light and the monochromatic are concerned. I suppose in one sense my interest in light stems right back to when I studied art history at A-level, and the likes of Leonardo, Canaletto, and Tintoretto. Chiaroscuro is key for me and was a moment where the light bulb went on and remained with me. I have a love of the old masters, especially the Italians who specialised in chiaroscuro, coupled with the investigation and invention of science. The way they use light is phenomenal. It is also symbolic of innovation. It really is key because I couldn't do my process without light.

For me it's about highlighting, stopping, looking and observing. No matter how many times you visit some of these locations, you don't actually see it all. Especially the things that you're not meant to see, like the stairwells, they are there as a function quite often, even though they are magnificent. I hope the illumination within my pieces helps people to stop and look at things they might not have otherwise noticed.

Works-in-progress in Lindsey’s studio

Can you tell me about what you’re working on right now? How has the 2 week residency at Ushaw Historic House & Gardens influenced this work? What are your aspirations?

There are a couple of books from the library that I was really drawn to, one of which was Ecclesiastical Ornamentation by Pugin. I think we laughed about it at the time because it was a catalogue of all the details or features you could get for your chapel, all hand-drawn, almost like an IKEA catalogue of the day. They didn't do things by halves!

There was also a book that compared architecture from the 15th century to the 19th century. They drew me in because of their graphic detail. I want to look at some of those details and how I could take embossing to be part of my process and to fuse the architectural aspects with the education aspects in my practice. One of the books they showed us at Ushaw was a first edition of Darwin's Origin of Species. I really want to celebrate the hidden collection, architecture, and the content of those books. The work is still very much evolving!

Books from Ushaw Library

And finally who are your artistic inspirations? How have they influenced the ways you approach your own work?

An artist who I have loved over the years is Susan Hiller. She had a show at Tate Liverpool, I think it was in the late nineties, and it really touched a nerve with me. She did have a history link to anthropology and collections but it's more how she displayed her work. She'd burnt some of her paintings and put them in test tubes. She was big on installations and storytelling through her work, it was all linked to untapped resources. Her work raised questions and the installations looked like museums. She passed away in 2019 but if I could, she'd be someone I'd love to sit and have a conversation with and to ask her about why she created her installations.

I’d also say old masters, like Leonardo or Canaletto, as they were real masters of the craft but also went to extremes to achieve what they did. I also think it's the people who've changed the route of things, someone as glorious as Alan Turing and the analytical engine and Charles Darwin and the battle he was having with religion and the theory of evolution.

I also love my network of printmakers. Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair and other places like Instagram have enabled this connection and network. I've got Liverpool contacts through my print studio but it's actually that broader network they facilitate that’s important.

Works-in-progress in Lindsey’s studio

Lindsey Moran’s work will be unveiled at Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair, 26 - 29 October 2023. Details here.

Find more Printmaking Inspiration here.

Discover more printmaking techniques here.

Thanks to our partner Ushaw Historic House, Chapels & Gardens.