Interview | FUNGAI MARIMA

Fungai Marima is a Zimbabwean-born multidisciplinary artist and printmaker based in London. Her work is centred on using the human body as an archive, in which she explores her own lived experiences of identity, memory and trauma.

Fungai’s practice uses the body as medium and method to explore themes of the archive, displacement, memory and trauma. She uses an embodied approach incorporating traditional printmaking techniques with performance, sculpture and sound to explore corporeality, gender and heritage.

Could you start by introducing yourself to our readers who might not be familiar with you and your practice?

My practice explores ideas that are centred on looking at the body as an archive of trauma, displacement, identity, and how they are stored in our bodies. I'm really interested in finding alternative ways of communication through gestures, the body, and movement. I'm interested in archiving those types of language, such as how to communicate a traumatic experience? How does the body store that? For me, it's about actively using the body to communicate these experiences and memories.

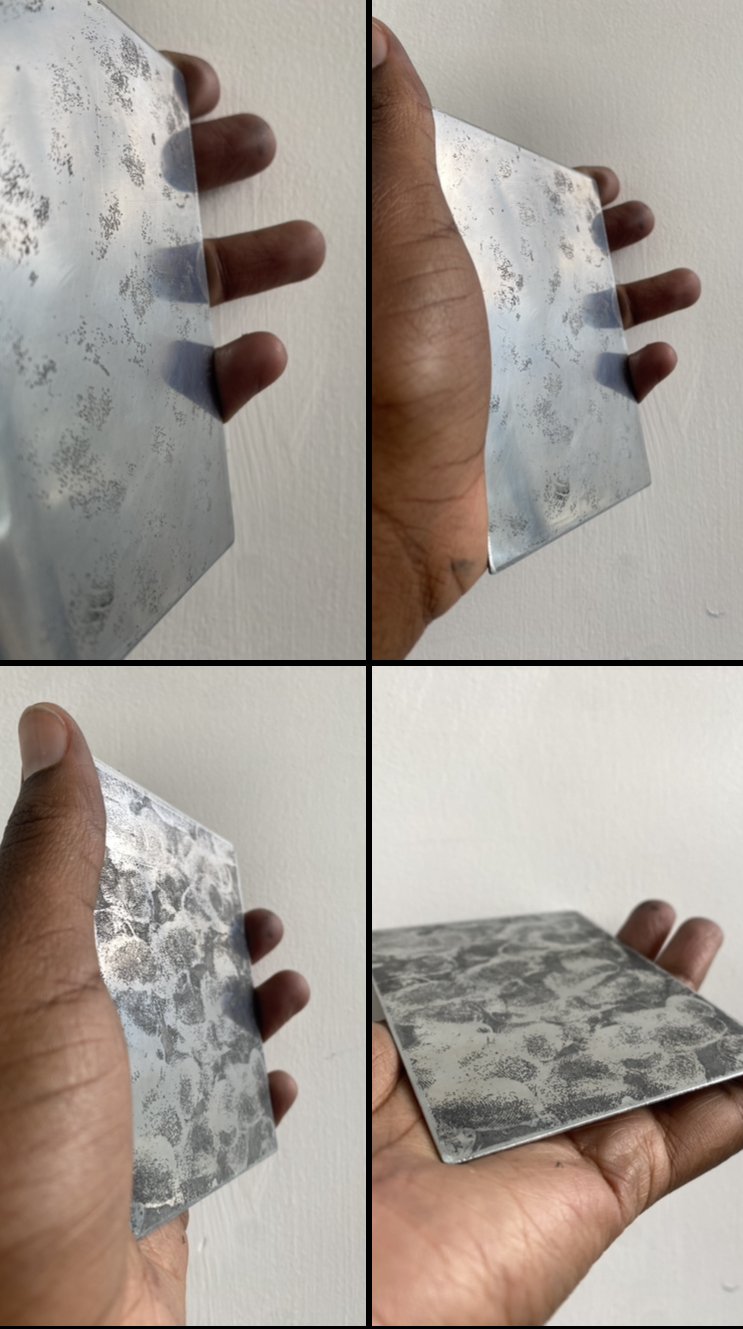

Body impression is integral to my practice and how I use different materials to extract information. For example, the body in movement, there's an element of performance. I use performance within my practice to engage with different materials. It could be another body, it could be a metal plate for etching, it could be paper. I like engaging with other materials to create these archives that you can then read later as prints, as text, in video or through a performance. I’m using the body as a tool to try and find different ways of archiving our experiences.

Test pieces by Fungai. Image courtesy of artist.

In Zimbabwe, I stumbled on art class in high school because it was a vocational subject. It wasn't part of the main body of subjects. I moved to the UK when I was 16 and I've actually been in the country for 16 years. I'm 32 now and because I actually ended up doing really well in my O-Level Art in Zimbabwe, I decided to pursue art. It was something that felt very natural to me.

I moved to the UK where I could do art A-level, I pretty much followed where I did well. With art, I was just naturally interested in it. It was a quiet place for me to think about the things I couldn't necessarily articulate using words. After my A-Levels, I continued on to do a foundation diploma at Havering College and I think that was the turning point because with encouragement from my lecturers I realised I had so much to say.

I then decided that there was something worth pursuing in this subject and that I would go and do an undergrad in fine art, specifically with painting and printmaking. The print room was where I could sit by myself, think about whatever was on my mind, and experience the magic of printmaking - where you don't really know what's happening as there are multiple elements to consider in the making, until you make the first proofs. This process of instinctively making was what drew me to printmaking and has allowed me to push my approach to making.

I did my undergrad and have now worked as a printmaking technician for about six years before I decided to do an MA in printmaking at Camberwell, in 2019-2020. However, between finishing uni in 2013 and doing my MA, I was mostly into painting. I would paint figures that would be captured jumping in the air, they were really expressive and big. Then, I didn't quite know what I was trying to release until I did the MA and then I realised that actually moving my body is important to my practice.

Feeling It Out, 2022, Film by Fungai Marima, created during a printmaking residency in Mexico.

You describe yourself as a ‘multimedia artist’ working across print, video, sound and performance. How do these different ways of making inform and expand your printmaking practice?

The body is at the centre of what I do and I realised that depending on the medium, I can't necessarily restrict the way the body should communicate. I decided that I wasn't necessarily just going to say I'm a printmaker or I'm a performance artist or I'm a sound artist or whatever it is. I just felt that I didn't want to cage myself or feel like I had to focus on one type of medium. I use the different mediums within my practice to inform the printmaking aspects. It's partly because in the print room you are constantly moving. There are so many sounds and materials you're engaging with, I think printmaking itself feels a bit like a performance.

The wax moulds I made in 2020 were actually made from moulding paper onto my body. I realised within printmaking that once you dampen a sheet of paper, you can pretty much do anything and it will hold itself until it's dry. There are so many possibilities within printmaking for me. So using performance or sound within my work are actually mediums that assist in making these prints come to life. I feel like they all work hand-in-hand. I can't necessarily focus on just making prints to explore everything else in my body that needs to be expressed from within.

Clip of Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Film by Fungai Marima.

The idea of sensorial space is really interesting and how you're grappling between the two dimensional and three dimensional to keep hold of a feeling in the body. What first drew you to printmaking? What was it about print as a medium to investigate the body that sparked off your early excitement in the studio?

With print, I work mainly with soft ground. Going back to the early magic I felt was that I could make an impression of something, I could hold it in a capsule of paper and have a record of that thing.

I felt that with painting, I wasn't really getting that sense of urgency or feeling. I was painting what I thought I was seeing, but with printmaking and the impressions I'm making, I don't necessarily know what I'm putting onto a plate or what I'm putting onto paper until I see it printed. So there's something about losing control and giving myself over to chance and I'm letting the body communicate. I can't necessarily have too much control over how the body communicates when talking about traumatic experiences, I just let it do whatever it needs to do and that is what it looks like.

Passage, 2022, Etching, 194 × 69 cm. Edition of 20.

I feel like the artwork really exists in print form so that it can be archived. I’m thinking about the history of printmaking and how it became popular in disseminating information. If I want to talk about things that are very human, how do you make that accessible? If I make one painting, it exists as one and only a selected few can view that. But if it's a print, I can make editions of this experience that I've just had or this idea that I am thinking about. I can use this as an archive and it can be seen by more people. That's going back to how revolutionary and transformative print was in terms of religion, political activism, printing onto small sheets of paper to easily disseminate the information. In terms of this work existing in print form, it is so that it can be its own type of archive. I'm not necessarily creating this artwork so that it can just live with me. It’s a way to distribute as much information as I can from working with my body.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Performance part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF. Photograph by Nicholas Harvey.

You recently performed Burn Out (Walking) as part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF in April 2023, could you talk more about this piece of work and how the performance became the process for making the print? What does it mean to you to create the print in front of a live audience and what happens after the performance when the print then becomes autonomous?

The walking performance I did at Bonhams was actually based on how most people I know right now are in constant cycles of burnout. How do you communicate what's actually happening in your own community and how are people then able to slow down? What type of language can you use to tell somebody to slow down? Burnout is time-based. It happens really slowly, like a fire burning out slowly. To talk about this idea of burnout, I had to really just take my time. I started thinking about what a normal working day looks like, usually 9 to 5. That's an eight hour working day for some people. I then thought about a performance where I would walk for 8 hours to see what that would do.

I was also thinking about the logistics of how to bring the print room into a different setting. I tend to use soft ground on my plates to make impressions, but it can be quite toxic and I was in a space where there isn't great ventilation. So I had to go back into the studio to think about different materials that I could use to still make impressions and for them to still be successful. I did a few tests at East London Printmakers using oil based ink and that worked. So I decided that I would walk onto two zinc plates using the oil based inks instead of the soft ground for the performance.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Performance part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF. Photograph by Nicholas Harvey.

It was important that the performance also existed in a different format. If you're thinking of Yves Klein or Adelaide Damoah who use paint to make body paintings on paper, it's very immediate. But it was important for me to go back to this idea of an accessible archive. How do you create an accessible archive in printmaking? It was important for me to have materials that would then allow me to turn this performance into a print.

I decided I would have two zinc plates that I would walk on for 8 hours, simply by just applying and removing ink from my feet and walking. It was important for there to be constant movement and to keep it simple. To push my body as far as I could and I felt like 8 hours would do that. It was actually my first live performance because I tend to work in the studio on my own and making impressions in front of a camera. This was the first time that I was preparing a plate in front of people, which I tend to do in a workshop.

Once I stepped onto the plates for the first time, I was now in my own world. Later in the day, I was starting to feel how physically it was taking a toll on my knees, on my feet, on my back. There were moments where I would just blank out and then come back, you know? It was really meditative. There was a time that I was even walking with my eyes closed because I knew my space. If you're walking in a space for a period of time, your senses and body’s spatial awareness kick in.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Performance part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF. Photograph by Nicholas Harvey.

The logistics for the prints themselves, which could easily get damaged, ended up becoming the most important part of the process. I walked for 8 hours and I needed to make sure they got to the studio safely. It was physically intense making them as part of the performance, but also making the prints themselves because they are so big, and it has actually taken quite a lot out of me.

This idea of the performance of printmaking extends the print room because I was then able to create and engage with these materials that I would normally reserve for the workshop. I've now created a space for myself where I can really expand this idea of print within my work, where performance feeds into the making and the making feeds into the ideas I want to bring to life.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Performance part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF. Image courtesy of the artist, photograps by David Mensah, 2023.

Within the history of printmaking labour is often hidden - no fingerprints are left on the edges of the paper. Within your work, labour is then made visible and this process being what is left in the image. This sense of the emerging image and the importance of building up tonality over time rather than the direct impression is interesting.

‘Becoming’ is actually part of my process in thinking through an idea or a theme. Printmaking has allowed me the ability to see things through and feel things through. I can't necessarily just say ‘this is what I want to communicate’ because I've got my body to communicate with, you know. So it is a process of becoming, seeing something come to life.

I’m having to collaborate with materials, to lend myself to how that material communicates or how the materials respond or react to whatever I do. I'm using zinc, a material that is actually quite soft. So if there's a knock or scratch on it that affects the print. But I'm actually okay with that because I'm using the body so I can let go and not be too precious with the materials that I use because it's important for me to just fully express my physicality the best way I can.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Performance part of Bonhams After Hours x WCPF. Image courtesy of the artist, photograph by David Mensah, 2023.

The material holds its own blemishes, like the body in a physical and psychological sense. It resonates with our earlier conversation around how trauma holds itself in the body and these become traces within the performance itself and on the plate. I think this physiological weight and the sense of care involved for you and the plate is very interesting.

I think care has actually come much later in my work because when you're so focused on wanting to get the idea out, I'm not giving my body the room to care because for me to actually see the work come to life, I've got to physically do it with my body.

Taking it back to my heritage of being Zimbabwean and African, a historian I was listening to on a podcast speaks on how African culture is understood through an active, not passive, body. For example, if you want to talk about fertility, there are dances on fertility, or if it's a celebration about something, you've got to physically use your body to be in touch with your environment, to mimic nature, to feel like you're in a cyclical relationship with your environment. That's also part of why I am now feeling like it's really important for me to explore what my body has got to communicate and why I've got to care for my body for me to be able to do those things.

To let go, release, or express and reveal some of these traumatic experiences, I've got to physically do that. Once you have put yourself in a position where you are exploring some of these feelings it is extremely important to also provide a space to truly and deeply care for yourself. That's what happened with Burn Out. I gave myself those 8 hours, whilst talking about this feeling of fatigue, the constant movement of my body actually allowed me to have introspection, to slow down, to take time.

The questions that you posed around caring for the body and yourself as a practitioner, are also deeply ethical questions around the practice of how we put in place structures to take care of both ourselves, our audiences, and subject matter.

Passage, 2022, Still from film by Fungai Marima.

I am also interested in how by placing your body and ink onto the surface of the plate to create an impression, your body is rendered into an image. We normally experience images on a vertical axis and your work subverts this. By walking or lying on the plate, you physically and conceptually reorientate the image to be horizontal. For you, what is the connection between the body, image, surface and horizontality?

I haven't necessarily considered this idea of the horizontal because instantly for me, when I'm thinking about the horizontal, I'm thinking about a passive body. I recall in making Passage, I was in the studio and I realised that the people I was collaborating with in terms of video and being in the studio, were mostly male. I recall taking off my skirt and my top so that I could get onto the plates and lie down. I had this overwhelming feeling of being watched. But once I got onto the plate, I was lying there and felt weightless. I left something there. At the time, the press went through my hair and I felt there was a release in that process.

Initially the idea of being surrounded by men that I felt were gazing onto me and I'm lying in an extremely passive position, while they are putting my hair into this press to the point where even if I wanted to get up, I couldn't because I was captive. I had to let go of any type of control and/or bias and I had to be actively passive in that moment. In the process of making that work, I believe I left a lot of heavy things on that plate and that's why it's titled Passage. It is a threshold from which you come from one space and into the other. The print is now evidence of the old, and my body is anew. In the making, I was actively passive.

Passage, 2022, Film by Fungai Marima.

For me, whilst you were lying down, you still were the power holder as the artist. In your work, the horizontal plane then has this sense of drawing people together, within this communal workshop setting, as opposed to the vertical singular. It starts to open up really interesting, subversive spaces around how we might traditionally consider looking within our history of the image. This sense of pushing away from normative experiences of art that might be perpetuated within art history.

There's an opening out of possibilities and there's something even just about the performance being on the ground, a horizontal plate simply placed on the floor. Everyone's eyes are drawn to the feet in this context where you are expected to look at the walls or artworks placed at the eyeline. In this sense, the horizontal is not passive but about reactivating or reclaiming this space.

When people were coming into the performance, they were forced to look down and I did notice that sometimes people didn't want to look but they had to. There was a plate on the floor that just looked black because of the black ink that I used. You had to get close to see what I was doing.

I find that really interesting, this idea of the horizontal plane that you're talking about, where you're bringing people to come to this space or giving a new way of viewing, or an alternative way of experiencing artwork. I'm also always thinking about how to orient materials when I am making, going back to this idea of making impressions with the body. Prints that I made in 2020, I'm physically falling onto plates. I'm putting the plate on the floor and intentionally falling onto them.

You've mentioned the importance of the archive within your work. Your prints become tactile documents of time and records of the performance. Could you expand on the relationship between intaglio print, archiving, and the body?

Intaglio, being specific to how I use soft ground, allows me to make an impression. That is where the importance is for me in terms of how I move my body or being able to see what I am doing with my body through the particular process of soft ground. I have found that with intaglio printmaking, there's a process of becoming. I've got to plan and think about the type of metals I'm going to be using or even in terms of time as soft ground at some point dries out. There's an element of immediacy. By the time I actually engage with the plate, it is extremely intentional for me to be able to communicate movements or gestures of the body. I require materials that allow me to leave these traces but also a material that is strong enough to hold, whether it is the weight of my body or a material that will be able to to get as much detail of my impressions. Also to be strong enough to go through the process of etching and inscribing.

I think the idea of inscribing is quite integral actually, because I was reading this book by Susie Orbach called Bodies, and she talks about how our external experiences feed into our physical. She talks about how everywhere humans go, they will try and inscribe their body in terms of understanding themselves and their identity. Intaglio allows me to do that, it allows me to inscribe my body onto a material for it then to exist as an archive.

Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Etching, 100 × 140 cm, Edition of 10.

Archives are collections or masses of documents or objects. They also become a mode of storage and are normally in between the personal and public, in relation to people, institutions or organisations, and I wonder if these questions appear in your work?

I have thought about archives in different formats, one specifically thinking about identification. At this moment, I am a Black woman, a Zimbabwean-African, at the age of 32, who resides wherever I do, and I live in Europe, in the UK, I am assigned within my identification. I'm part of a classification and I could easily be deemed an object. I have thought about this specifically in relation to a Khoi woman called Sarah Baartman, who was exhibited in Europe because she was deemed ‘exotic’. She existed as an archive that was exploited for all of those things. So this is constantly running within my artwork in terms of location, just even being in the art world, being in the print world, and being a Black woman in the print world.

If I'm to think of my heritage alone as being Zimbabwean, you know, there's a skull of a prominent Zimbabwean spiritual medium who is in the British Museum. I go back to this idea of inscribing and that's why it's important I use my body. Although the body has been used in ways of exploiting, taking and experimenting, I'm using my body to comment on that but then have control over how I use my body. I’m subverting this idea of how bodies are even archived or how they are used within museums or institutions. Thinking about the politics of archives, they are not necessarily always accessible, sometimes intentionally inaccessible. I want to create an archive of my own that is accessible for different people to see.

Fungai standing beside Burn Out (Walking), 2023, Etching, 100 × 140 cm, Edition of 10. Photograph by Lucy J Toms.

We’re delighted that Burn Out (Walking) is being exhibited as part of WCPF23. When your prints are publicly exhibited and take on their own autonomy independent of the performance, does this change the work for you? How does the personal and public intersect within the work?

When it's just on the wall, it's now an object, essentially. It's something that people can view but it's removed from the original intention. However, I have had conversations with people viewing it and they still do feel something. They might not really know the full story, but being able to just be in the presence of a body communicated in so many different ways allows me to see a part of myself in that, whatever that might mean. The process of making the artwork is the important aspect of the artwork. Once the print exists on the wall, it is an archive and an archive can be interpreted in so many different ways and I have to let it exist on its own.

And finally who are your artistic inspirations? How have they influenced the ways you approach your own work?

Ana Mendieta has been influential in how I think about artwork production and for it to not only be centred on sophisticated materials but how I can draw inspiration from my own body. Giving yourself over to and letting go of yourself to what the body wants to communicate through a gestural language and thinking about the traces of the body in space, land and material, allows you to stop and contemplate.

Donald Rodney, in particular one piece called In the House of My Father, in which he used his own skin and made this really fragile but strong little house. How we inhabit these bodies, how they protect us, how they are fragile but really strong, and how they can also really talk about the things that are happening in our lives in a really beautiful way. That piece is just so beautiful.

And then Janine Antoni and how she uses the body to talk about anything and everything. How labour is part of her practice and how an active body, in terms of really pushing the physicality of the body, in making work is really important. Pushing the boundaries of what the body can do and how far you can take it to communicate various things until you find that beautiful moment in the work and you know it's done.

Fungai in the studio. Image courtesy of artist.