Interview | Maite Cascón

Maite Cascón is an artist printmaker based in Madrid. She was awarded the Ushaw Residency and Acquisition Prize 2021 at Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair. The artwork produced as part of the prize will be exhibited at this year’s 2022 Fair and an edition will be put on display and acquired for Ushaw’s permanent collection. Maite is the first woman to be artist in residence at Ushaw Historic House.

Maite’s work centres around a world of figurative images that are full of symbolic references. By using satirical characterisation, she represents myths and forgotten traditions that challenge conventional behaviours, questioning inherited culture, beliefs, and patterns.

We are delighted to welcome you as the first WCPF Ushaw Historic House artist-in-residence, congratulations! Are there aspects of this residency and the historic house, chapels, library and gardens, which you are particularly excited about?

I'm really excited about the library because I work a lot with tales and storytelling from Northern Spain. I try to look at stories related to Catholic tradition with contemporary eyes. I'm interested in seeing how storytelling develops through time, and iconography is really interesting as it's basically like early surrealism. So I'm thinking about manuscripts, paintings, illustrations in the marginalia, architecture, sculptures, and the religious iconography of the Virgin Mary and the Saints because I get a lot of inspiration from that. I like to see the similarities between Catholicism and other religions as well, for example the iconography of the Virgin Mary is related to one of the goddesses of fertility from Egyptian mythology, Isis.

And you mentioned as well that you were interested in exploring the gardens?

I love nature and anything related to botanical illustration. In some of my prints, I put the figures on top of trees and the trees are almost like a ghostly presence. Nature also links us to a religious feeling, being overwhelmed by nature was a way people felt the presence of God. I’m interested in looking at plants and analysing them because the symbolism between all the plants is different. For example, lilies might symbolise peace, an oak tree for Celtics symbolises endurance, and in Spain rosemary symbolises good luck. So I'm very interested in the meanings of plants because they are a big part of the symbolism in my work.

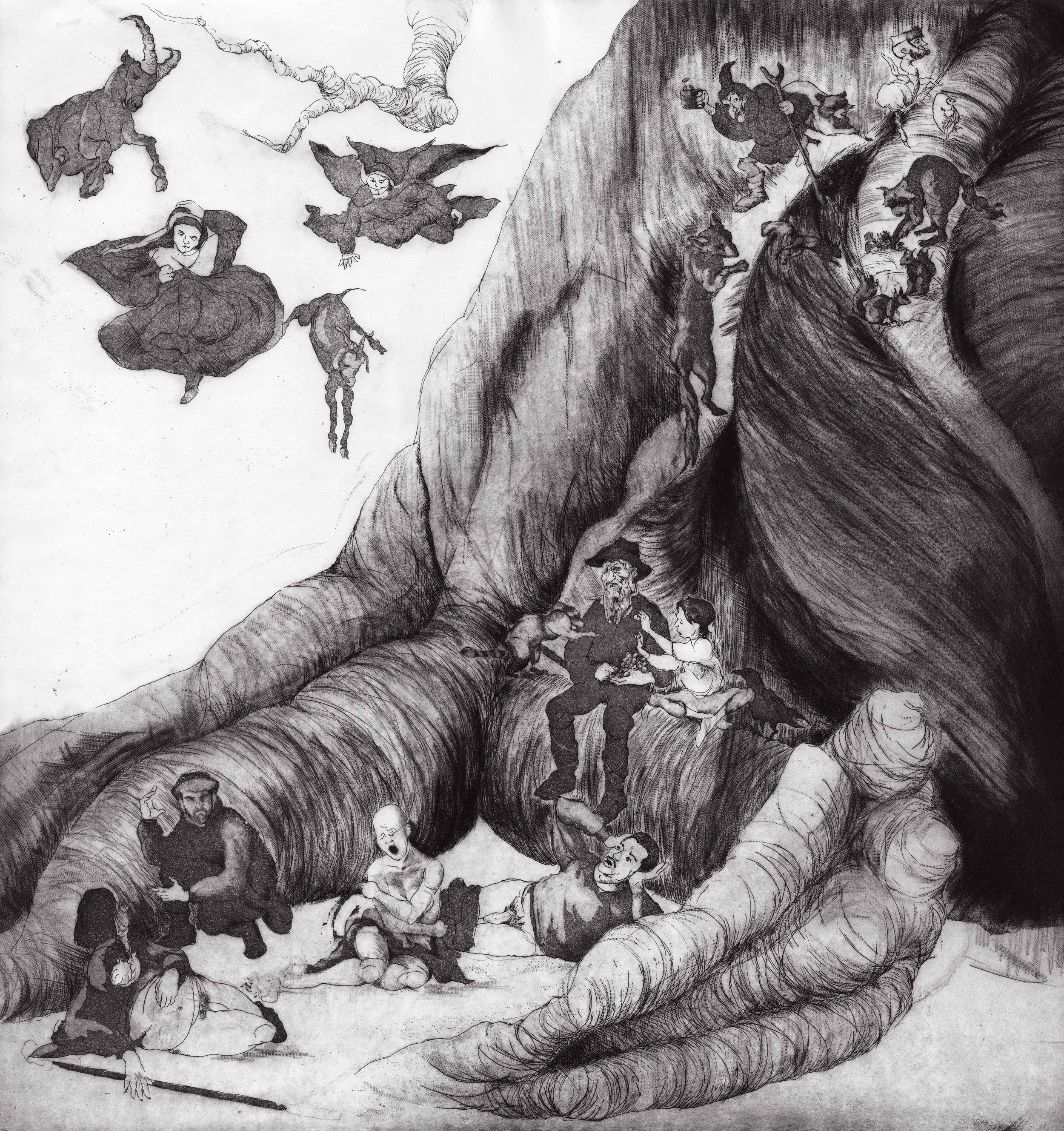

You also won the Woolwich Contemporary Printmaking Prize for your intaglio print ‘Tricksters Tree I’ (2020). Could you talk more about this piece of work and the inspirations of Spanish folk tales, feminism and symbolism?

It relates to witches or specifically nuns from a convent that were thought to be witches. The stories were written in the beginning to warn people, the witches were looked at as evil or something negative. If you look at the tales now, they have this feminist perspective. In the tale, the nuns go to save one of their own coven because she was being sexually assaulted in the forest. They killed the attackers and left their bodies. When the people from the nearest village found the bodies of the men, they took them to the nearest sacred place, which is where the nuns lived. Apparently in the tale, during the burial the nuns were laughing, which the people from the village thought was very strange. So the work started from these tales about the nuns not being Christian but instead witches. In the pilgrimage route near Galicia in Northern Spain, I think there is the original convent, which is now in ruins. People thought this area of the convent was full of witches, so it's interesting to see a physical place related to the tale and to follow the history in relation to the real world.

This folklore about witches in Northern Spain is still nowadays a very interesting subject to look at because it challenges the stereotypes of women, which were very strict until the 1980s. The witches, which were a symbol of evil within a woman, when you look at it now, were just women not living by the standards of those times. It's interesting to see the real side. A lot of the women were elderly and didn't have anyone to help them cope with life. People from the villages tried to get rid of them to stop being a burden for the community and it's very sad. It was just a way to expel people from the community because they were not seen as useful anymore.

I think it is really fascinating because witches, which is a word or a method of oppressing women, becomes a way for them to express their freedom. It’s interesting the way you are subverting this and commenting on patriarchal oppression of women. And you've touched a little bit on this but could you talk more about how you're relating printmaking and folklore tales to a contemporary context?

Spain is a Catholic country and if people were not from Christian faith, they would be accused of witchcraft. It’s interesting to see the paganism behind a lot of the traditions that are still alive in Northern Spain come from pre-Christian cultures. In a way it relates to something more contemporary because most of these festivities related to paganism were also banned during the Franco dictatorship. Ávila is a city and community that has a carnival where people dress with animal skulls and wear dresses made of leaves. It's very interesting that it comes from the Celtics as well as pre-Christian cultures. When Franco was in power, all of these rituals were banned and so the same happened with the spread of Christianity in Northern Spain, people who practiced those rituals or beliefs would be accused of witchcraft because it didn’t fit in with Catholicism at that moment.

I have the feeling that these tales are not well known. People abroad don’t relate pagan tales to Spanish Culture. This is folklore wisdom that has been forgotten or tried to be erased. I tried to revive the tales and cultures that are really important for the identity of the different people and areas. For example, in Galicia they have their own language and culture where the witches are very present. This is also the same in the Basque country, they have a completely different mythology with a lot of pagan creatures. I think at this time the country is more open to revisiting these tales and cultures from the past, which help us to understand about the identity of a place.

However, with the rise of the extreme right there is a discourse trying again to establish a fake homogeneity of Spanish culture. Whereas, Spain is particularly rich because of its cultural differences between regions. The same extreme right parties are slandering and fighting against the current feminist wave that happened all over the world since the Me Too movement. There was a specific and quite famous sexual assault trial in Pamplona called ‘The Wolf Pack’ that cause a series of feminist protests, which forced the government to change the law in the country. At this same time, I found the tale of the flying nuns and I was struck to see that these sorts of crimes that sadly happened appear in these old tales and were avenged in the form of witches making their own justice for women. I found some similarities in the tale of the flying nuns as a group of women trying to defend one of their own, in relation to what happened a few years ago with the massive protests trying to defend the victim against ‘the wolf pack’, when the law wasn’t good enough at protecting women.

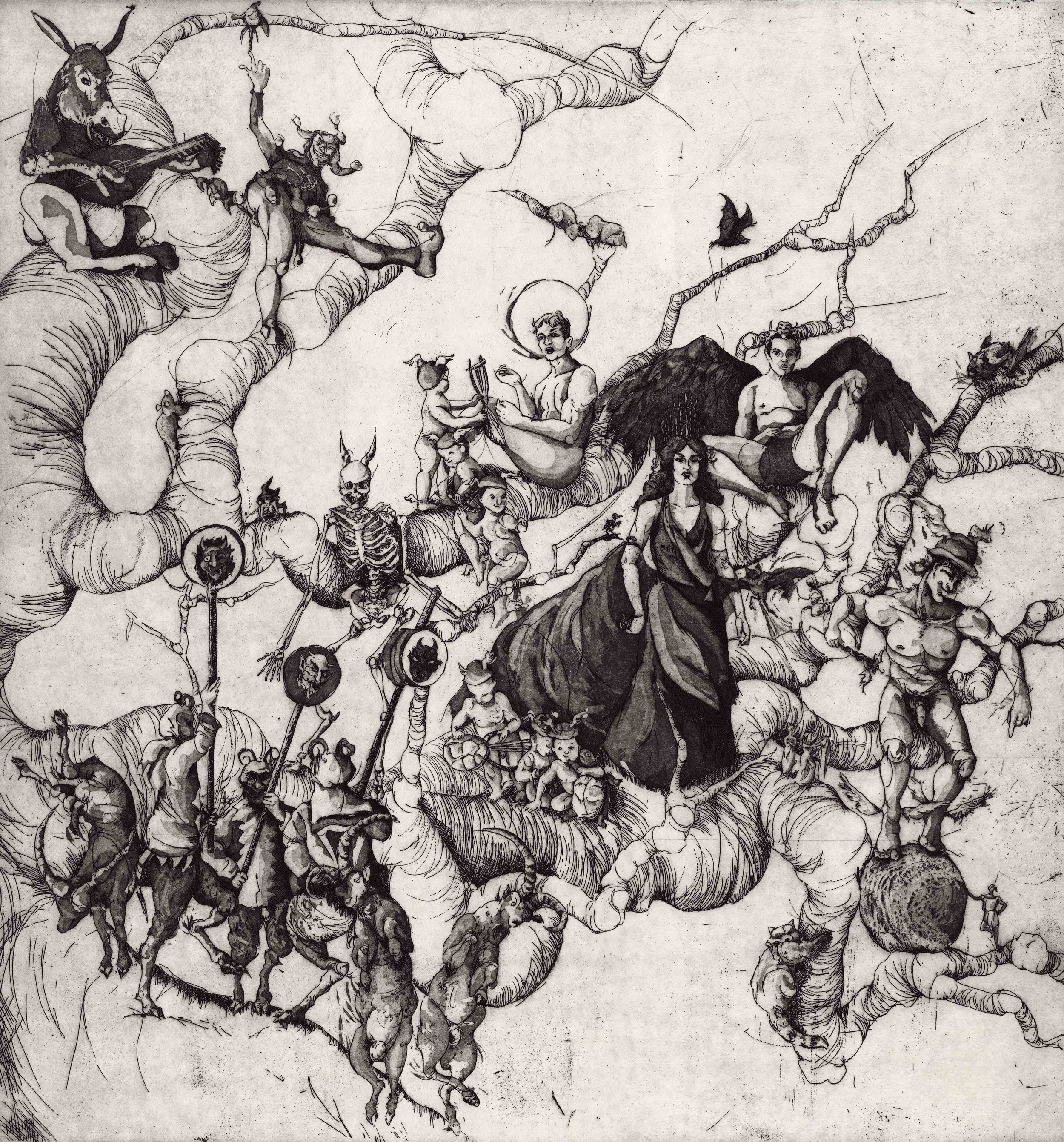

You also talk about The Trickster as recognisable in folklore wisdom, tales and carnival figures and its association with the archetype of The Shadow. Can you tell us more about The Trickster and its relationship with The Shadow?

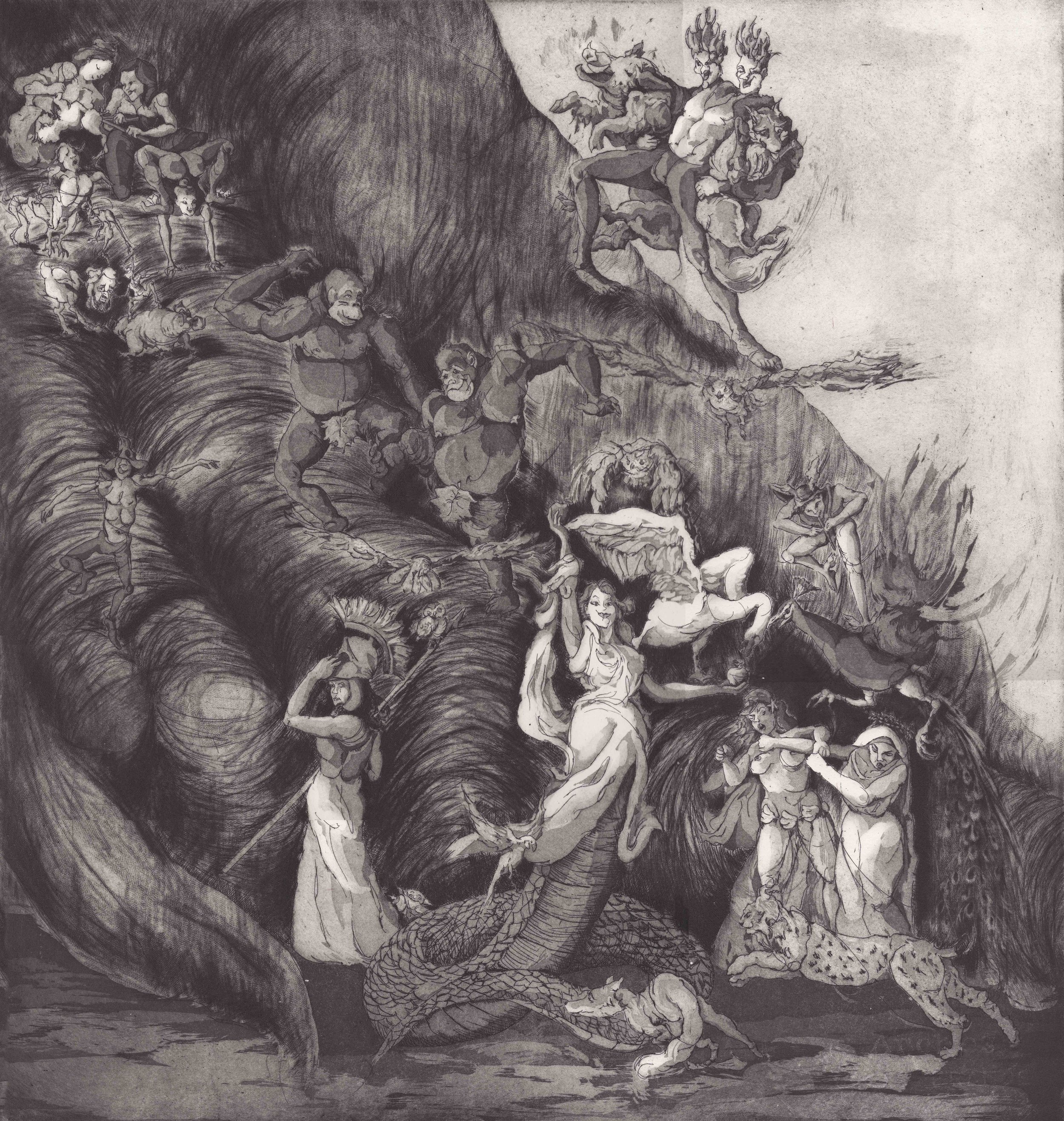

In the process of doing the project ‘The Shadow Tree’, I could see that some of the characters in folk tales that embody the Shadow shared similarities with the Trickster archetype too. The witch is one of the stereotypes of the Shadow because it’s all the neglected qualities of a woman. The witches were portrayed either as elderly, mischievous and jealous women, or if they were naked, sinful and tempting young girls. They were portrayed as the opposite of what a woman should be. So in a way, they were the archetype of the Shadow. When you look at the stories, they also behave like the archetype of the Trickster. So in a lot of storytelling, one character could be both things. For example in ‘The Shadow II’, I have a print that represents three witches: one of them is masturbating with a branch from the tree, while the other one is monstrously shapeshifting, and the third is looking at three little girls playing with bones and other objects related to witchcraft. I decided to depict the witches with girls in this way because in a lot of stories the intervention of an evil witch is what makes the girl protagonist grow up.

So, the witch is a good example of how a stereotype portrays both archetypes. They can be represented as evil characters subverting the moral order but you can also find stories and legends where they used their cunning for the sake of fun, or to try to improve their poor life status, as in my print ‘Tricksters Tree I’.

I'm interested then in how the motifs of The Trickster and The Shadow manifest in the processes you use in your practice, such as the monochromatic approach and the use of installation?

At the beginning, the sketch is when I research all the details. I sometimes try to divide the prints or plates into different cultures. So for example, when you look at 'The Trickster’, the print that has an eel is based in Norse mythology. Then on the opposite side, there is a woman that is representing Baubo, who is one of the tricksters in Greek mythology. She's basically a womb with legs. This is a great myth. So I tried to separate the plates by different cultures but at the same time, I wanted to communicate that they are all related as well. They all talk about the same concept.

I deliberately did ‘The Shadow Tree’ with very dark tones. When you see the whole installation, it comes across as a very dark project. The main point is to confront fears. So I wanted to make those plates really dark and the background obscure. Aquatint is the perfect technique to achieve this. With The Trickster, I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted it to be clearer and have more line work. I focused in the composition on the curves and the ribbons. I wanted a lot of movement in the composition for it to feel vivid and active because of the features of the Trickster archetype. For example, Hermes in Greek mythology, one of his features is that he is very fast. So with ‘The Trickster’, I tried to make the lines very fresh to capture that sense of movement.

What draws you to intaglio as a method?

I think it's an addiction! I think it's because you don't really know how it's going to look at the end, so it's a mystery. When you see your image in reverse, you're always surprised with the feeling of ‘I don't really know how it's going to look’. It's also the whole process. When I'm drawing with hardground, I love the way the needle goes so easily, so smoothly. I really like the fine lines you can get with an etching needle and the way of drawing and sketching when you're doing a plate is really pleasant. When I finish the line work and I do the aquatint, I think it is the most challenging point because you have to measure the time in the acid bath and try to be really accurate. It’s a challenge but I think the challenge is what I like! You almost feel like a scientist in a lab. I also love the mezzotint process, some of the effects you can get, it's just amazing.

Can you talk to us about what you are working on right now?

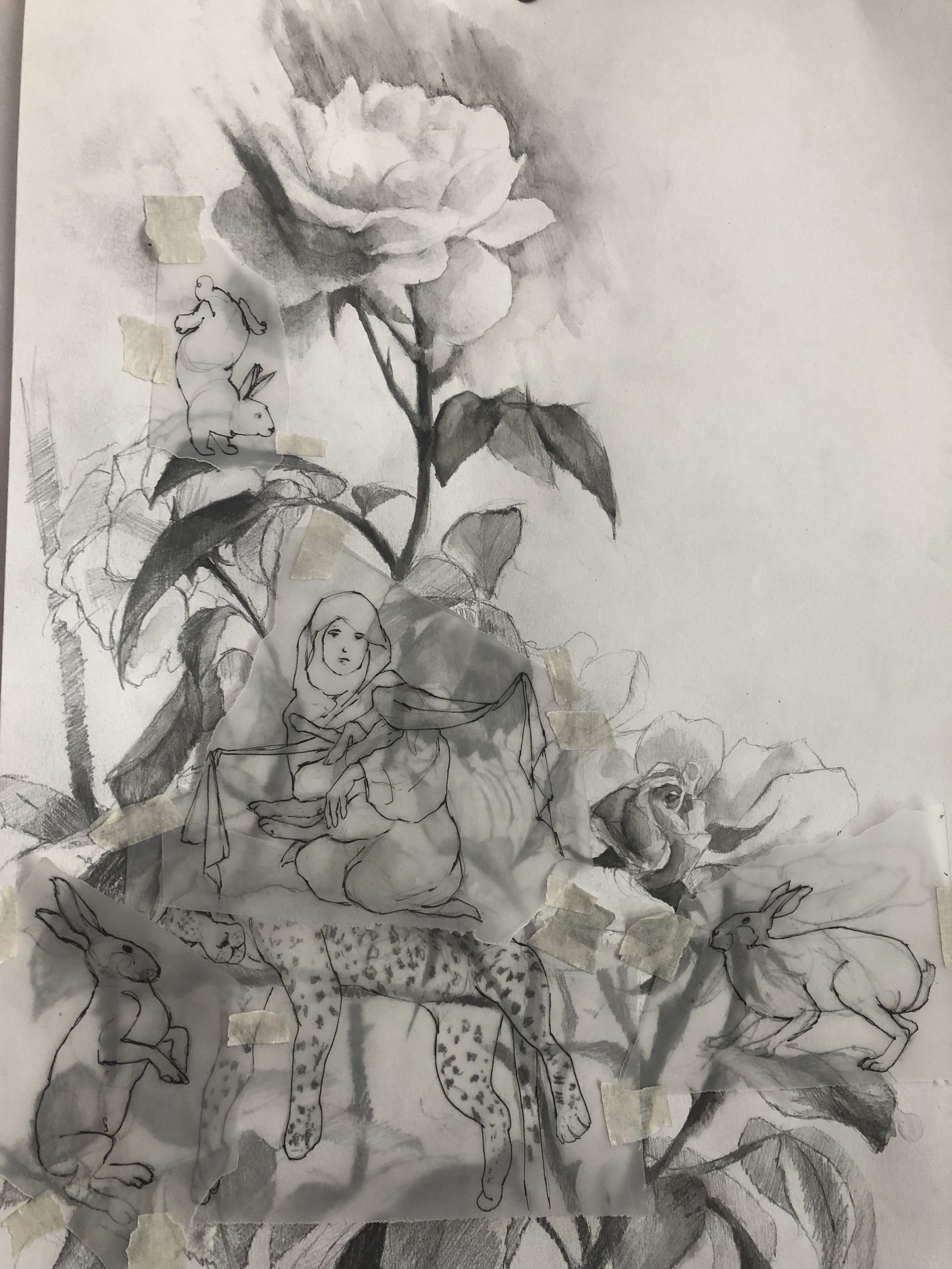

There is so much stuff that I am really interested in at Ushaw but I think one of my favourite parts has been the main Chapel. There is a panel of a rosebush that says ‘Mystic Rose, pray for us’, and I knew, because of my Spanish background, the rose symbolised ‘The Passion’ when Jesus died on the cross and the red rose means blood. But here, I realised the rose was the same symbol for the Virgin Mary. I remember when my mum used to pray with a rosary that had a small medallion of the Virgin on it, and I never made the link in my head ‘why rosary’ and that the rose is a symbol of the Virgin Mary. So the rosebush is one of the symbols I might use. They also have beautiful statues of the Virgin Mary and I am drawn to the symbolism related to fertility. It wasn’t something I have previously focused on, however, here there's so much symbolism surrounding this concept. I also didn’t know that rabbits were a symbol of fertility and it's really funny because they’re everywhere!

And finally, Who are your artistic inspirations? How have they affected the ways you approach your own work?

I love Nicola Hicks. She works with sculptural installations but I love all her imagery. She also works with the shadow archetype and a lot of her work is related to darkness. So I think some parts of my practice resonate with hers. She also uses a lot of symbolism and animal figures, who are like the protagonists of her work. I really admire Paula Rego, again she uses a lot of animals and symbolism. She also has a strong feminist perspective in her work (the abortion series for example) and I have realised that my work is also very based in female figures. For example in The Trickster, I enjoyed making the flying nuns (‘Tricksters Tree I’) and Baubo (‘Tricksters Tree VIII’) the most, but the whole project is full of trickster goddesses or female figures.

Find more Printmaking Inspiration here.

Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair, 03 - 06 November 2022. Details here.

Thanks to our partner Ushaw Historic House, Chapels & Gardens.